Ancona

bringing Italians over and back

http://www.serventi.com/histories/ServNar2.html

Ancona was the first North Atlantic passenger steamer of the Italia Line, and its most-employed ship on that route before World War I. Built by Workman, Clark & Co. in Belfast, it was 482 feet long, 8,188 tons in size, and its triple expansion engines provided it with a speed of 16 knots. Ancona began service in 1908, and, between then and the outbreak of the First World War, carried a roundtrip total of 98 thousand passengers between Italy and New York, over 90% of them in steerage. Like most of its North Atlantic contemporaries, Ancona stopped at more than one port in Europe; it was also one of a sizable minority of vessels servicing more than port on the North American side of the ocean (New York and Philadelphia; for Ancona, the latter was mainly a departure port), (Voyage Database).

Italia Line

Italia Società di Navigazione a Vapore was one of several Italian passenger shipping lines plying the North Atlantic, that were started around the turn of the 20th century, and eventually merged into the oldest and biggest such Italian line, the NGI (Navigazione Generale Italia). Italy was then among the largest and fastest-growing exporters of overseas emigrants, most of them bound for North America. In the 1890s, about two-thirds of Italian immigrants to the United States crossed the Atlantic on non-Italian carriers; by 1908, the traffic was split about 50-50 between domestic Italian oceanic steamship companies and their foreign competitors. (Bonsor, Keeling, p. 23, and sources used on pp. 28-29, Voyage Database).

Maiden Voyage

On its maiden voyage, Ancona set off from Genoa on March 26, 1908 with 59 passengers in steerage and 9 in cabin. Most of it passengers boarded in Naples, which Ancona departed on March 28 with 341 in steerage and 23 in cabin. A total of 432 passengers were thus landed at New York upon arrival on April 10, but this traffic was dwarfed by the numbers on the April 23 return journey to Europe. From New York (910), and Philadelphia (1,343), the ship was nearly 90% filled to capacity with a total of 2,253 passengers, overwhelmingly Italians in steerage. (Data from Voyage database, U.S. passenger list).

Two-way migration between Italy and the United States

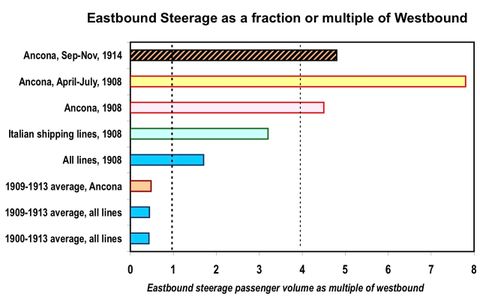

The back-and-forth pattern of late nineteenth century emigration from Italy helped popularize the term golondrina (swallow), in its classic conception, the “peasant who left Italy in November after harvest for flax and wheat fields of northern Cordoba and Santa Fé [Argentina]…and in May returned to Piedmont [Italy] for the spring planting” [Thistlethwaite, p. 25]. Most Italian migrants to the United States, however, crossed the ocean only once (to reach America) or twice (to later return to Italy for good). In the 1900-1914 period, repeated back and forth movement was proportionately higher from northern Europe (see map here, and Keeling, Repeat, p. 172). There was a significant exception to this return movement comparison, however: Because so many Italians did intend to return to Italy with savings, they were particularly reactive to labor market conditions. Employment conditions strongly influenced the migration patterns of all ethnic groups, but Italians in America, over-represented in cyclically vulnerable industries such as construction, tended to react even more sharply than most others to joblessness or the likelihood of it, by returning to their family homes in Italy where the costs of being without work were far lower (Keeling, pp. 202-05). During the recession years 1904, 1908 and 1911, eastward return movement to Mediterranean ports (half or more of which was to Italy) was 55% of westward flows, compared to 32% for the 1900-13 period as a whole. For the rest of Europe, the eastward rate was 42% during those recessions versus 29% for the overall period (Voyage database). The 1908 recession was the most severe of these cyclical slumps, and Ancona was among the ships whose passenger traffic was most powerfully impacted by the eastbound surge of 1908, as shown in the graph here:

Source for graph: Voyage database

World War I and Ancona

When World War I broke out in early August of 1914, Italy stayed neutral, but many Italians in America felt needed back home and they soon returned in large numbers, including on Ancona (see graph above). Another eastward surge followed Italy’s entry into the war in late May of 1915. Ancona’s next three voyages averaged over 1,300 eastbound steeragers each, and then the ship’s final U.S. departure, on October 16, 1915, carried twelve hundred Italian reservists (New York Times, October 17, 1915: “1,200 Italians Sail for War”). Shortly after departing Italy for New York again, Ancona was sunk on November 7, off the coast of Tunisia, by submarine U-38, operating under the Austrian flag. This exacerbated diplomatic tensions (New York Times, December 15, 1915: “Austria’s Reply”) between the United States and the Central Powers (e.g., Germany and Austria) already strained due to the sinking, without warning, of the Lusitania the previous May. Negotiations, and the German “Sussex Pledge” of May, 1916 reduced further U-boat activity, and helped keep America out of the war, until unrestricted German U-boat attacks resumed in early 1917.

Principal sources (citation details here):

Keeling, Repeat Migration

Keeling, Business

Thistlethwaite

U.S. Passenger lists at EllisIsland.org

Mass migration

as a travel business

Mass migration

as a travel business